The London – based Gallery, Stair Sainty, at TEFAF Maastricht 2018, showcasing Magnificent Artworks.

JEAN-BAPTISTE OUDRY (Paris 1686 – 1755 Beauvais)

Le Pêcheur et le petit poisson, 1739 (The Fisherman and the little fish from La Fontaine’s fables)

Oil on canvas: 120 x 172 cm Signed and dated lower-centre: J. B. Oudry 1739

Provenance: Collection of the artist; Louis-François Mettra’s inventory after death in 1763: ” un peint tableau peint sur toile par Oudry représentant un Pêcheur…prisé 60 livres” [Mettra was agent for the King of Prussia and it was probably intended for the collection of Frederick the Great]; Collection, Mme Steinberg, Paris, from the 1950s; to her nephew M. Garnier ; to Galerie Aveline and Galerie Segoura, Paris; Private collection United Kingdom.

Exhibited: Salon of 1739, as ‘Un Tableau en largeur de 5. Pieds fur 4. De haut, représentant la Fable du Pêcheur & du petit Poisson tirée de la Fontaine: Ce Tableau appartient à M. Oudry.’

Literature: Jean Locquin, Catalogue raisonné de l’oeuvre de Jean-Baptiste Oudry peintre du roi (1686-1755), in Archives de l’Art français, nouvelle periode, VI, 1912, no. 383, as Le Pêcheur et le petit poisson, with the 1739 Salon catalogue description above; Hal N. Opperman, Jean-Baptiste Oudry, 2 volumes, Chicago, 1972, p. 355 as ‘Le Pêcheur et le petit poisson, present whereabouts unknown. 1.3 x 1.62 m. Ex. : Salon of 1739. Bibl. : Locquin, no. 383.’ Francois Marandet, in the Symposium, Art français et allemand, Paris, 2008, pp. 265-281 (for the reference to Mettra’s inventaire9

The Enchanted Home

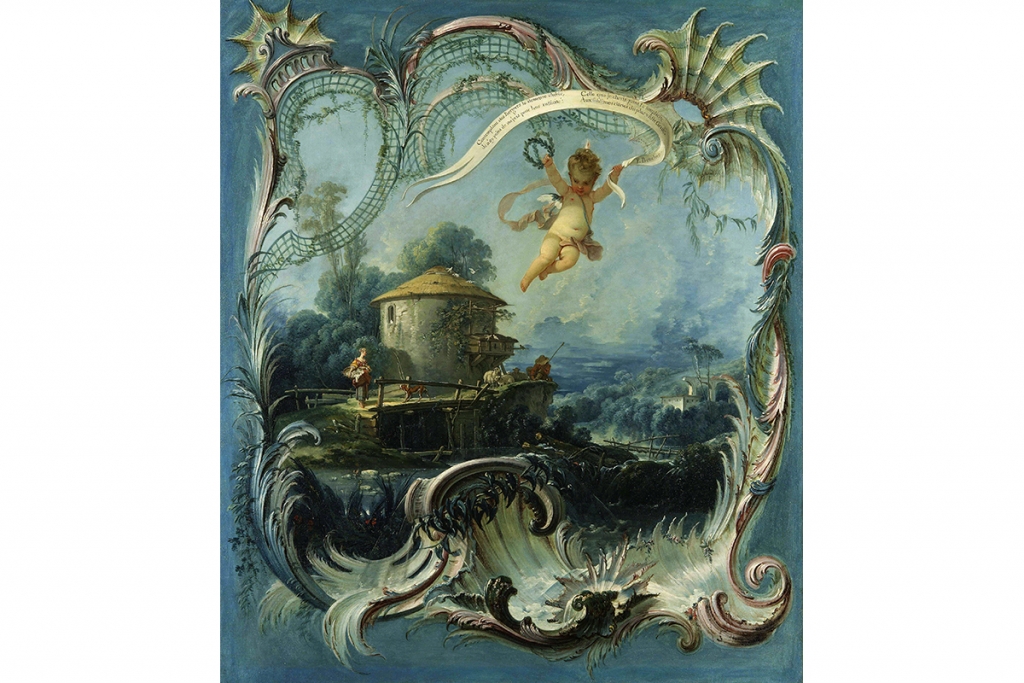

A Pastoral Landscape surmounted by Cupid

©Courtesy Stair Sainty Gallery – London.

FRANÇOIS BOUCHER (1703 – Paris – 1770)

The Enchanted Home : A Pastoral Landscape with Cupid’s tribute to Mme de Tencin, c.1740-42 Oil on canvas: 127.5 x 109.5 cm

Inscribed: “Contemplant des Bergers / la demeure chérie / Je n’ay point de mépris / pour leur rusticité : / Celle que je chéri joint la simplicité / Aux sublimes clartés du /plus vaste Génie. F. Boucher”1 – translates as Contemplating the shepherds/ cherished abode / I do not disdain them for their rusticity:/ for the one I cherish joins simplicity/ with the sublime brightness of/ great genius. F. Boucher

Verso: three labels reading ‘3544’, ‘541’, and ‘un paisage de Boucher / pour la p… de Mad. / De Tencin / no. 12’

Provenance: Claudine-Alexandrine Guérin de Tencin ; ? 1749 to her heir Jean Astruc ; Veil-Picard heirs, Paris; Private Collection, Paris; Sale Artcuriel, Paris, 3 August 2007; Stair Sainty Gallery; Private collection, Canada.

This entrancing work, hitherto unknown to scholars, marks something of a departure for the artist; evidently intended as a decoration, it is painted with a degree of attention that Boucher normally reserved for major commissions of the highest quality. It was, perhaps, the importance of the lady to whom this work is dedicated, identified by Alastair Laing as the brilliant and seductive Mme de Tencin, which inspired Boucher to devote so much attention to this substantial painting, exceptionally placed within an ornate rococo border as if it was set in an imaginary boiserie. There is a chinoiseries enclosed in a painted rococo framework by Boucher (formerly in the Rothschild Collection, in 1915) with a single figure surrounded on a more modest scale than the present work, but this is clearly a more purely e decorative work than the present painting. Two other chinoiserie overdoors en camaïeu bleu, now divided between the Davids collection, Copenhagen, and that of the Earl of Chichester, have a lighter, decorative rocaille border.

The painting may be dated both on stylistic and historical grounds to circa 1740-42, by which date Mme de Tencin and Boucher were already well-acquainted. The artist was hoping to attract the attention and patronage of the Swedish Count Tessin, charged by his royal mistress, Queen Louise Ulrike, with purchasing the very best examples of contemporary French art for her expanding collection. It is perhaps hardly surprising that Count Tessin was drawn to the vivacious and brilliant Mme de Tencin; even though then aged nearly sixty she was still able to attract leading intellectuals and public figures with her wit and learning. Among the works that Tessin purchased from Boucher was a second version of the celebrated Leda and the Swan (1742) now in the Swedish National Gallery, while he also commissioned the artist, a brilliant draftsman, to illustrate his own book of fables, Faunillane ou l’Infante Jaune (1741), inspired by his admiration for Boucher’s pretty young wife. Only a few copies of the book were produced and when Tessin was recalled to Sweden in the same year he gave the plates to Charles Pinon Duclos, who following a wager that he could write a different story to fit them, produced the romance of Acajou et Zirphile.

Claudine-Alexandrine Guérin (1682-1749) was the daughter of a prosperous lawyer, Antoine Guérin, Seigneur de Tencin, President of the Parliament of Grenoble and representative of a successful noblesse de robe family. Initially promised by her parents to the convent where she was educated, Alexandrine protested strongly at being forced against her will to make profession at the age of sixteen, a stand she repeatedly reiterated. Following the death of her father in 1705 and despite her mother’s remonstrances, she was able to transfer to a more liberal convent where Alexandrine’s predilection for a more worldly life led her to embark upon the first of many affairs, with Arthur, Count Dillon, an Irish Jacobite and soldier who had risen to the rank of General, fighting for France in the War of the Spanish Succession. Supplying evidence that she was coerced into making profession she was able to obtain a Papal dispensation in 1711 to be relieved of her vows (a process completed the following year), for which she was evidently thoroughly unsuited.

She promptly left to join her older sister, Mme de Ferriol, where during a brief affair with the elderly Abbé de Louvois, Philippe, Duke of Orléans, Regent of France during the minority of Louis XV, also fell briefly for her attractions. At Louvois’ death she forged a relationship that proved more important to her career, when Abbé Guillaume Dubois, not yet a Cardinal, the Regent’s first minister, took her as his mistress; Dubois considerably advanced her brother Pierre’s ecclesiastical career while she helped him in his ongoing struggle with the pro-Spanish faction led by the Duchess du Maine. Pierre Guérin, after being appointed Abbé of the magnificent Romanesque basilica of Vézélay, obtained the Prince Archbishopric of Embrun in 1724 (he was translated to Lyon as Primate of the Gauls in 1740), a Cardinal’s hat and the position of Ambassador to the Holy See in 1739, before being appointed to the post of First Minister to the King in 1742.

Unusually for a woman of her time Alexandrine proved to be adept at managing her finances; with the help of Dubois, Henault and the banker Law she managed to triple her fortune in less than a year, enabling her to acquire the barony of Saint-Martin on the romantic Ile de Ré. Financially independent, she had by 1727 established her Salon in the hôtel particulier belonging to her sister’s husband at 22 rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin, until the Ferriol family sold it in 1730. She then moved to a new apartment at 390 Rue Saint Honoré, near the Oratory, where she received her visitors on Tuesdays and Fridays; following the death of the renowned hostess, Mme de Lambert, in 1733, Alexandrine quickly attracted a distinguished circle. Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, Charles-Irénée Castel de Saint-Pierre, Pierre de Marivaux, and Alexis Piron were among the habitués, along with Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke and Philip Stanhope, 1st Earl of Chesterfield. By her relationship with the brilliant soldier, the Chevalier Louis-Camus Destouches, she was the mother of the philosopher, collector and encyclopédiste Jean le Rond d’Alembert born in 171713 but the suicide in her house of another lover, Charles-Joseph de la Fresnaye in 1726, led to her temporary imprisonment in the Châtelet and Bastille prisons (where, in the latter she became acquainted with Voltaire, whom she nonetheless detested). Fortunately she was absolved from blame and released, becoming an adept but more discreet political intriguer bent on furthering the career of her friends, lovers and family.

In 1742 her considerable political influence was exemplified by her successful promotion as the King’s mistress of Marie-Anne, Marquise de la Tournelle (created Duchess of Châteauroux); with the latter’s premature death two years later, Mme de Tencin’s advanced Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, Mme Le Normant d’Étoiles, later to gain renown as Mme de Pompadour, whom she had been nurturing since had first appeared in Parisian society as a nineteen year old beauty in 1740. It was perhaps in Mme de Tencin’s Salon that the future mistress of the King first became acquainted with the work of Boucher, whose greatest patron she was to become.

Alexandrine’s influence had begun to decline, however, and by 1746 she had withdrawn from society. Although Mme de Tencin’s career had been in many ways dependent on the favours of powerful men, she also maintained numerous female friendships notably with Marie-Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin (1699-1777) to whom Alexandrine’s salon visitors transferred their loyalties after her death, the Marquise de Châtelet (Voltaire’s lover, scientist and mathematician), and Louise, Mme Claude Dupin, friend and patron of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In her last years grossly overweight and suffering from deteriorating eye-sight, she moved to an apartment on the Rue de Vivienne, where she died on 4 December 174914 attended by her last lover, the celebrated doctor, Jean Astruc (1684-1766)15 to whom she left her estate. A talented author, Mme de Tencin’s novels survived changes of fashion and taste to find renewed popularity when they were republished in Paris in 1825.

A label on the reverse demonstrates that our painting was intended to be installed in Mme de Tencin’s house, probably that in the [rue des Saints-Augustins] where she spent the early 1740s, although it is uncertain how it was displayed. The inscription to the gracious hostess, to whom the artist offers his homage, was intended to be legible,compositions, so it seems more likely to have been placed where this could be easily read. The extraordinary attention Boucher dedicated to landscape and figures as well as the intricate border also leads one to suppose the artist was expecting it be given close inspection by Mme de Tencin’s visitors. A series of small nail holes set 2-3 cm from the edge, suggests that it was attached to some structure rather than hung directly and that this band around the edge was covered, perhaps, by some kind of framework or boiserie.

The principal elements repeat those used by the artist several times throughout his career; the colombier (pigeonnier or dove house) appears in at least seven landscape compositions from 1739 onwards (the first being Le Vieux Colombier, Hamburg, Kunsthalle), while the dog is repeated precisely in the Pont of 1751 now in the Louvre. The naked cupid, an appropriate symbol in a work dedicated to lady so practiced in the art of love and who holds aloft the scroll bearing the dedication, can be seen in an identical pose in Apollo Revealing His Divinity to the Shepherdess Issé, signed and dated 1750. The young woman selling eggs, a common sight on the streets of Paris but whose erotic associations would have been immediately recognisable to Mme de Tencin’s sophisticated friends, appears in a drawing engraved by Ingram and is close in pose to the young woman in Frère Luce (Moscow, Pushkin Museum) from 1742. The seated shepherd boy placed in the very centre of the painting, can also be seen in a drawing, while the distant landscape and brilliant sky with light, scudding clouds, resembles that in the Landscape with Watermill and Temple from 1743 (Barnard Castle, The Bowes Museum). While the subject and provenance are now secure, the painting’s whereabouts since Mme de Tencin’s death in 1749 remains a mystery. Despite its inclusion in the illustrious Veil-Picard collection it nonetheless escaped the attention of scholars until its present startling revelation as a work of the highest quality, a sublime example of this great rococo painter at his most inventive.

The extraordinary career of Francois Boucher was unmatched by his contemporaries in versatility, consistency and output. For many, particularly the writers and collectors who led the revival of interest in the French rococo during the last century, his sensuous beauties, coquettish milkmaids and plump cupids represent the French eighteenth century at its most typical. His facility with the brush, even when betraying the occasional superficiality of his art, enabled Boucher to master every aspect of painting – history and mythology, portraiture, landscape, ordinary life and, as part of larger compositions, even still life, sometimes combining aspects of each discipline a masterly ensemble .

Boucher had been trained as an engraver, and the skills of a draftsman, which he imbued in the studio of Jean-Francois Cars, stood him in good stead throughout his career; his delightful drawings are one of the most sought after aspects of his oeuvre. As a student of Francois Le Moyne he mastered the art of composition – although in later years he was to deny his debt to Le Moyne – while the four years he spent in Italy, from 1727-1731, gave him a knowledge of the works of the masters, in the classics and in history, that his modest upbringing had denied him.

While in Rome Boucher had been encouraged by Vleughels to go out into the campagna and draw scenes from nature. Alastair Laing has suggested that Boucher did not paint any of the surviving views of the environs of Rome while a student there but instead, on his return to Paris, used these drawings as the basis for the painted landscapes of the early 1730s. Similarly, the figures in these compositions were often inspired by and, on occasion, directly based on Bloemart figures that he later engraved. Both his early Italianate views and the later landscapes share a common characteristic; they appear to be set on a three-sided stage, with virtually no horizon. No attempt is made to lead the eye into a distant view, as Claude had deliberately set out to do a century earlier. When Boucher was commissioned to design a set for the play Issé and again in another stage design, he did so without any appreciable change in his approach. A rare exception to this is the very beautiful landscape now in the Pushkin entitled Frère Luce, signed and dated 1742, in which the small figure of La Fontaine’s friar stands before his hovel in the right foreground while the landscape to the left disappears towards some distant hills. A compositional structure the artist has employed to advantage in the present painting.

On his return to Paris Boucher’s energy and talents quickly brought him public renown and, in 1734, he gained full membership of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture with his splendid Rinaldo and Armida (Paris, Musée de Louvre), a bold rococo statement which, while showing his awareness of the famous composition of Domenichino in the French Royal Collection, is marked nonetheless with the very distinct characteristics of his own, maturing style. Although he painted a handful of subjects taken from the Bible throughout his career, and would always have first considered himself to be a history painter, his own repertoire of heroines, seductresses, flirtatious peasant girls and erotic beauties was better suited to a lighter, more decorative subject matter as well as the hedonistic taste of his patrons.

His mastery of technique and composition enabled him to move from large scale tapestry cartoons (he worked throughout his career for both the Beauvais and Gobelinstapestry factories, becoming director of the latter in 1755), to intimate masterpieces such as the Diana Resting (Paris, Louvre) or Leda and the Swan (Los Angeles, Private Collection) and the occasional scene from everyday life such as The Luncheon (Paris, Louvre), with its elegantly dressed figures grouped around a well-laid table.

Enormously successful and widely admired, Boucher’s output was prodigious. First patronized by the Crown in the 1730s, he executed numerous royal and princely commissions until his death in 1770, working particularly for Louis XV’s mistress, the Marquise de Pompadour in each of her several palaces, having succeeded Carle van Loo as Premier Peintre du Roi and Director of the Royal Academy. Always ready to utilize his talents in other fields, he designed stage sets for theatre and opera and provided drawings to be used as designs for figures at the Vincennes and later Sevres porcelain factories. As a teacher he was much loved by his many students, who included Fragonard, Le Prince, Deshays, Brenet, Baudouin, Lagrenée, and Madame de Pompadour herself. Even David, a distant cousin, in his earliest surviving works with their colourful rococo palette, was clearly influenced by Boucher. Not since Le Brun had a single French artist held such a monopoly on the imagery of a particular society or left such a mark on the arts of his time.

STAIR SAINTY GALLERY

38 Dover Street.

London WIS 4NL