A Great and Deeply Moving Solo Exhibition

Cotton shirts, steel, and plaster; dimensions variable

© Doris Salcedo ©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

This May, the Fondation Beyeler will be the first museum in Switzerland to devote a comprehensive solo exhibition to the Colombian artist Doris Salcedo (*1958), presenting eight major series of works from different periods of her career. On 1300 square metres, the presentation brings together around 100 individual pieces, among them key works on loan from major international institutions as well as rarely exhibited works from private collections. In her objects, sculptures and site-specific interventions, Doris Salcedo addresses the experiences and repercussions of violent conflicts across the world. Even though her works often take specific events as their starting point, they are of universal significance and validity. The artist’s work often revolves around reflections on loss, individual suffering and the ways societies process collective grief. Her installation Palimpsest, 2013–2017, has been on view at the Fondation Beyeler since October 2022.

Installation viewin the Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2023

© Doris Salcedo ©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

Doris Salcedo grew up in Colombia’s capital Bogotá, which she describes as an epicentre of catastrophe. Persistently confronted with her native country’s political power structures and widespread human suffering, Salcedo developed a distinct social and political awareness, leading to works that lend form to the ideas and emotions triggered by these experiences. Rather than simplistic depictions, Salcedo searches for people’s shared feelings and understanding. In her own words, she says:

“What I’m trying to get out of these pieces is that element that is common in all of us.”

A key work in the exhibition, A Flor de Piel, 2011–2014, consists of hundreds of rose petals stitched together to form a filigree shroud spreading in folds over a large area of the floor. The work’s point of departure was a crime committed against a Colombian nurse who was tortured to death and whose body was never found. The title A Flor de Piel is a Spanish phrase that combines references to flowers and skin, and is used to describe emotions of such overwhelming intensity that they become exposed and visible to others, for example through a reddening of the skin. For Salcedo, the act of sewing the petals together is an important part of the work, in which the fragility of life is uniquely visualised.

(detail) Rose petals and thread; dimensions variable – Solo Installation view

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2023 ©Doris Salcedo ©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

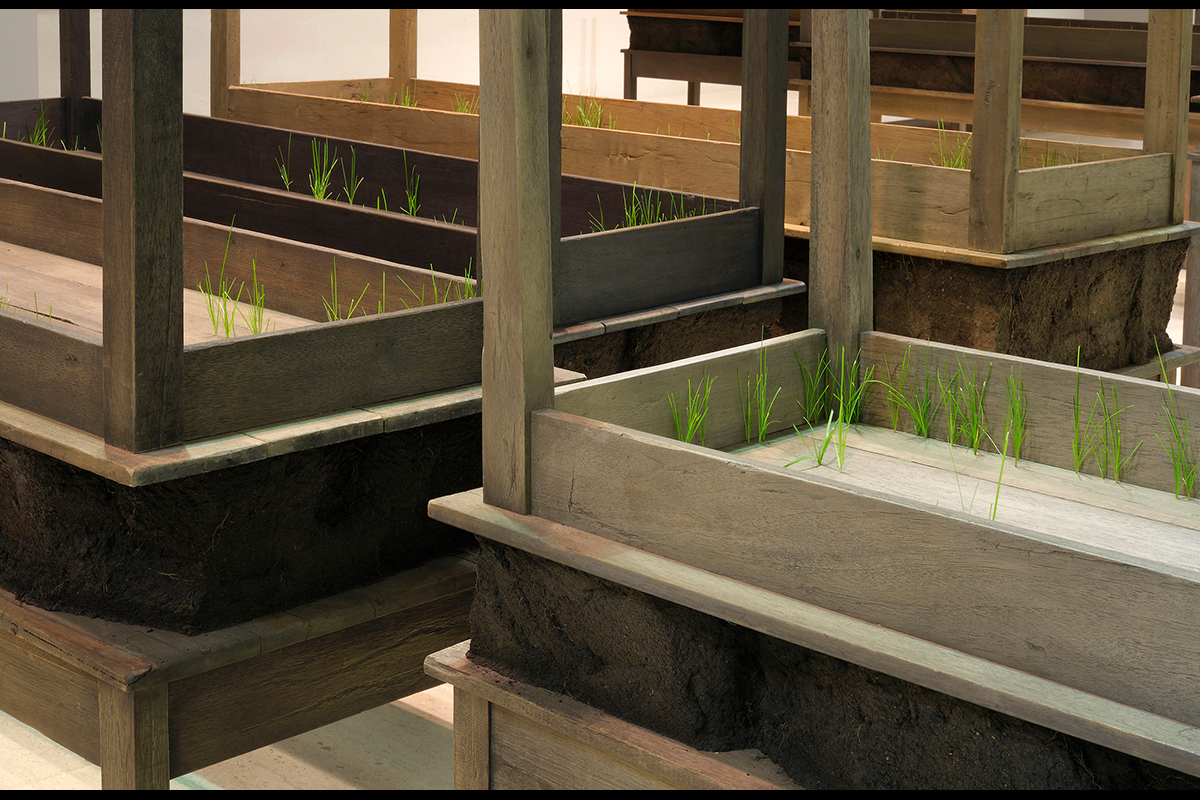

The adjoining room displays the lined up tables of Plegaria Muda, 2008–2010. In 2008, Salcedo researched gang violence in Los Angeles and found that victims and perpetrators often shared comparable socioeconomic circumstances and came from similarly underprivileged backgrounds. Based on this observation, the large-scale installation consists of coffin-sized tables stacked one upside down above the other in pairs, each separated by a layer of earth. Delicate blades of grass sprout from this soil and grow up through the table tops. Each of these pairs stands symbolically for one of hundreds of perpetrator-victim dyads whose fates remain tragically entwined. Reminiscent of a freshly laid-out cemetery, the work also reflects the suffering of Colombia’s grieving mothers looking for their missing sons in mass graves. Plegaria Muda, which translates to “Silent Prayer”, brings to light the universal significance of dignified individual burial and leave-taking. At the same time, the work also bears witness to how, just as grass grows over a grave, the events of the past fade from memory as life goes on.

Wood, concrete, earth, metal and grass, 166 parts; dimensions variable Installation view

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2023 © Doris Salcedo ©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

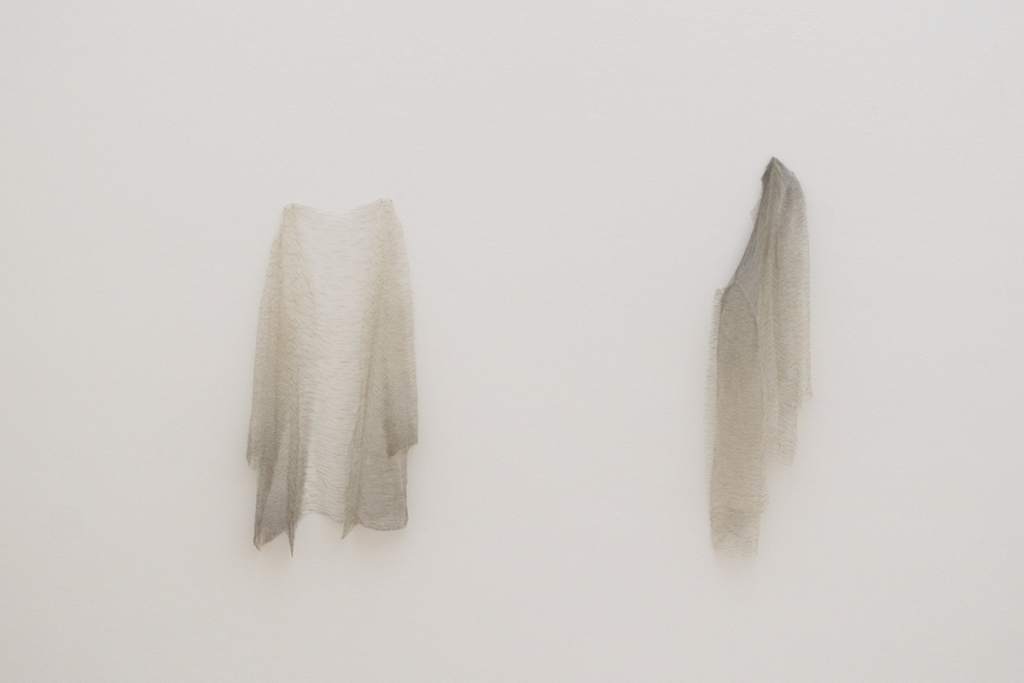

Disremembered, 2014/2015 and 2020/21, illustrates several important aspects of Salcedo’s oeuvre: the almost immaterial, barely tangible specter-like forms of human scale appear to float against the wall and only reveal themselves up close. The shirt-like garments, which Salcedo designed following the pattern of her own blouse, compose of pale silk threads pierced by tiny, blackened needles. The idea for the Disremembered series developed when the artist spoke with mothers who had lost children to armed violence in Chicago’s toughest neighbourhoods. The women’s ever-present and inconsolable pain is signified by the more than 12,000 fine needles woven directly into the fabric interspersed in a deliberate, irregular pattern.

Sewing needles and silk thread; dimensions variable – Solo Installation view

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2023 © Doris Salcedo ©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

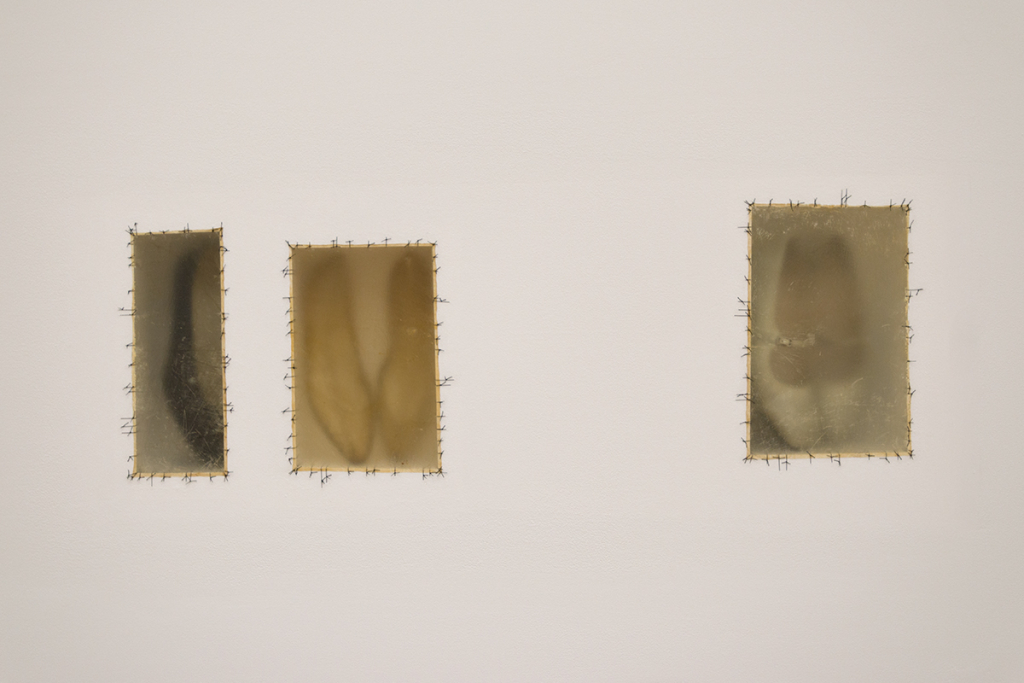

This polarity of delicacy and violence is typical of many of Salcedo’s other works. Atrabiliarios, 1992–2004, features worn shoes set into niches in the exhibition wall sealed off with stretched cow bladder that clouds our view of them. Salcedo thereby seeks to preserve the memory of their former owners; women who have become victims of enforced disappearance in Colombia.

Installation viewin the Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2023

© Doris Salcedo ©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

In the series Untitled, 1989, various pieces of wooden furniture have been encased in concrete. For this work, Salcedo spent time with the families of victims of Colombia’s persistent violence and civil war. She used the victims’ domestic furniture and clothing, rendered useless by their death, to symbolise their absence.

Wooden armoire with glass, concrete, steel, and clothing; 183.5 × 99.38 × 30.8cm Installation view Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2023 © Doris Salcedo ©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

Unland, 1995–1998, goes back to interviews conducted by Salcedo with orphaned children in northern Colombia who had witnessed the murder of their parents. The series joins together various pairs of different half-tables using a blend of silk and human hair to illustrate the fragile equilibrium of families torn apart by violence.

Wooden tables, silk, human hair, and thread; 90 × 245 × 80 cm Solo Installation view

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2023 ©Doris Salcedo ©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

Untitled, 1989–93, was created in response to two massacres that took place in 1988 in Northern Colombia on the banana plantations of La Negra and La Honduras with the sculptures being composed of white, cotton shirts in plaster and impaled by steel rebar. Alluding to the absent human body, the shirts reference the standard dress of workers on these plantations as well as funerary dress for the dead. Stacked in different quantities, these sculptures also appear to take measure of the loss of human life.

Cotton shirts, steel, and plaster; dimensions variable

© Doris Salcedo ©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

In the large-scale installation Palimpsest, 2013–2017, Salcedo focuses on the refugees and migrants who over the past 20 years have drowned attempting the dangerous crossing of the Mediterranean or the Atlantic in search of a better life in Europe. She spent five years researching the names of the victims that appear and fade on the sand-coloured slabs covering a floor area of around 400 square metres. Doris Salcedo’s works often require years of planning, research and fieldwork leading to complex and meticulously planned processes of conceptualisation. The horrors she addresses are never shown directly. Instead, she deliberately selects materials and means of expression that obliquely visualise terror and dread while also encompassing beauty and poetics. With her work, Doris Salcedo aims to build bridges between the suffering and sorrow of human existence on the one hand and hopes and aspirations on the other hand.

Hydraulic equipment, ground marble, resin, corundum, sand and water; dimensions variable – Installation view Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, 2023 ©Doris Salcedo ©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

Doris Salcedo

Doris Salcedo was born in 1958 in Bogotá, Colombia, where she still lives and works today. She studied painting and art history at the University of Bogotá, then sculpture at New York University in the early 1980s. In 1985, she returned to Colombia, undertaking numerous journeys around her country to meet survivors and relatives of victims of brutality and violence. Her resulting awareness of and sensitisation to the themes of war, alienation, disorientation and displacement have informed her work ever since.

Fondation Beyeler, Riehen/Basel, Switzerland 2023

©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

Salcedo found attention among others with large-scale installations such as Untitled, 2003, Shibboleth, 2007, and Plegaria Muda, 2008–2010. Untitled, 2003, produced for the 8th International Istanbul Biennial, consisted of about 1550 wooden chairs stacked between two buildings to address the history of the migration and displacement of Armenian and Jewish families from Istanbul. For Shibboleth, 2007, at Tate Modern in London, she created a long snaking fissure that ran the vast length of the Turbine Hall, allowing social segregation and exclusion as well as separation to be experienced in spatial terms. The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago presented a first retrospective of her work in 2015. Last year, a solo exhibition was devoted to her in Glenstone, Maryland. Doris Salcedo was featured at the Fondation Beyeler in a 2014 collection display with works from the Daros Latinamerica Collection. In 2017, organised by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Palimpsest was shown at the Palacio de Cristal in Madrid and subsequently at White Cube in London. This installation has been on view at the Fondation Beyeler since autumn 2022, its first presentation in the German-speaking world. Salcedo’s most recent work Uprooted, 2020–2022, is currently on display at the Sharjah Biennial 15

(detail) Rose petals and thread; dimensions variable Presented as part of the D.Daskalopoulos Gift to Tate

© Doris Salcedo ©Photo: Patrizia Tocci

The exhibition has been curated by Sam Keller, Director, and Fiona Hesse, Associate Curator, Fondation Beyeler.

An exhibition catalogue featuring essays by Fiona Hesse, Seloua Luste Boulbina and Mary Schneider Enriquez as well as a foreword by Sam Keller and poems by Ocean Vuong is published by Hatje Cantz Verlag, Berlin.

©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023

FONDATION BEYELER

The museum in Riehen near Basel, Switzerland is internationally renowned for its high-calibre exhibitions, its outstanding collection of modern and contemporary art, as well as its ambitious schedule of events. The museum building was designed by Renzo Piano in the idyllic setting of a park with venerable trees and water lily ponds. It boasts a unique location in the heart of a local recreation area, looking out onto fields, pastures and vineyards close to the foothills of the Black Forest. In collaboration with Swiss architect Peter Zumthor, The Fondation Beyeler is constructing a new museum building in the adjoining park, thus further enhancing the harmonious interplay of art, architecture and nature.

© Doris Salcedo ©Photo: FG – arttravelint / F.Glz. 2023