CHRISTIE’S FALL PRINTS AND MULTIPLES SALE ACHIEVES $13.2 MILLION

THE FIRST AI WORK TO BE SOLD IN A MAJOR AUCTION

ACHIEVES $432,500

HIGHEST SALE TOTAL IN RECENT YEARS

New York – The four-session Prints and Multiples sale of over 350 lots concluded today with the AI portrait of Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy from the art collective Obvious selling for $432,500. The work was won by an anonymous phone bidder after a battle between three phone bidders, an online participant in France and one gentleman in the room. The total for the sale was $13,239,750, one of the highest totals in recent years, and was anchored by the top lot, Andy Warhol’s Myths which achieved $780,500. The sale witnessed global participation with registered bidders from 34 countries across Asia, the Americas, Australia, Europe, and the United Kingdom.

Is artificial intelligence set to become art’s next medium?

AI artwork sells for $432,500 — nearly 45 times its high estimate — as Christie’s becomes the first auction house to offer a work of art created by an algorithm.

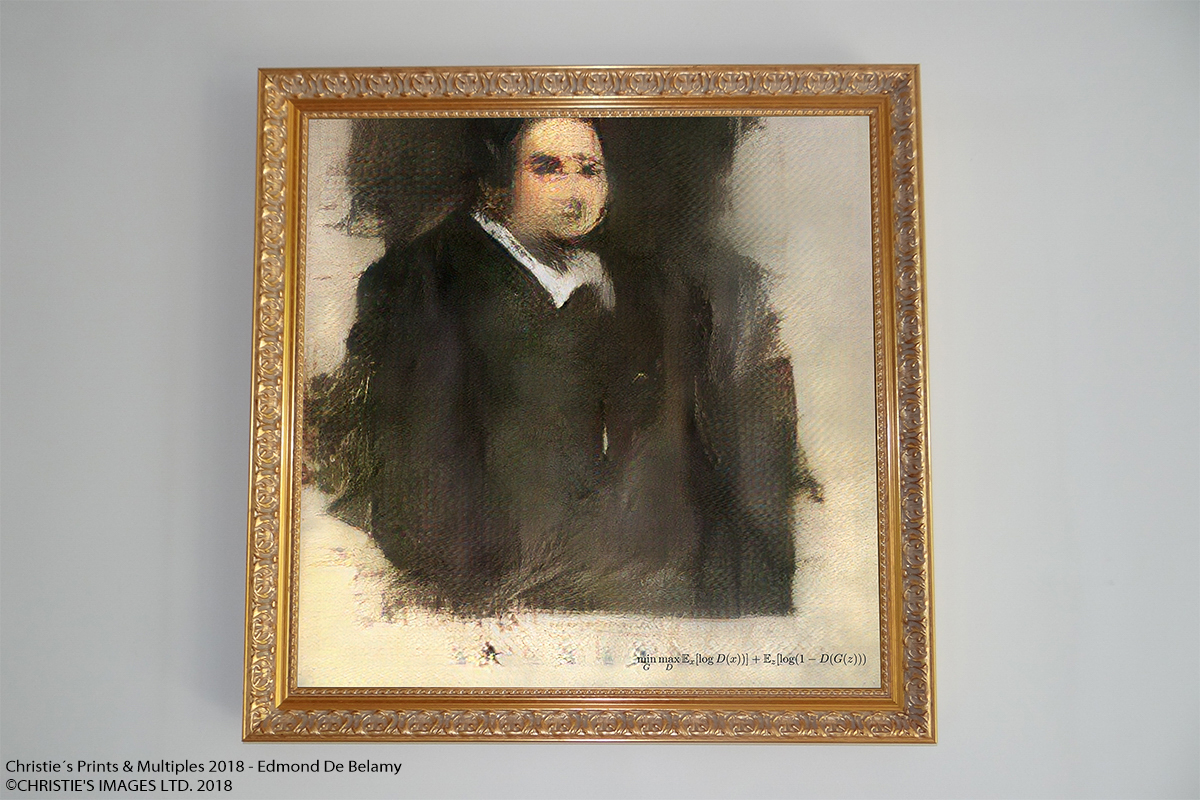

The portrait in its gilt frame depicts a portly gentleman, possibly French and — to judge by his dark frockcoat and plain white collar — a man of the church. The work appears unfinished: the facial features are somewhat indistinct and there are blank areas of canvas. Oddly, the whole composition is displaced slightly to the north-west. A label on the wall states that the sitter is a man named Edmond Belamy, but the giveaway clue as to the origins of the work is the artist’s signature at the bottom right. In cursive Gallic script it reads:

This portrait, however, is not the product of a human mind. It was created by an artificial intelligence, an algorithm defined by that algebraic formula with its many parentheses. And when it went under the hammer in the Prints & Multiples sale at Christie’s on 23-25 October, Portrait of Edmond Belamy sold for an incredible $432,500, signalling the arrival of AI art on the world auction stage.

‘The algorithm is composed of two parts,’ says Caselles-Dupré.

‘On one side is the Generator, on the other the Discriminator. We fed the system with a data set of 15,000 portraits painted between the 14th century to the 20th. The Generator makes a new image based on the set, then the Discriminator tries to spot the difference between a human-made image and one created by the Generator. The aim is to fool the Discriminator into thinking that the new images are real-life portraits. Then we have a result.’

‘We found that portraits provided the best way to illustrate our point, which is that algorithms are able to emulate creativity’ — Hugo Caselles-Dupré of Obvious