A VOYAGE THROUGH THE GOTHIC REALM

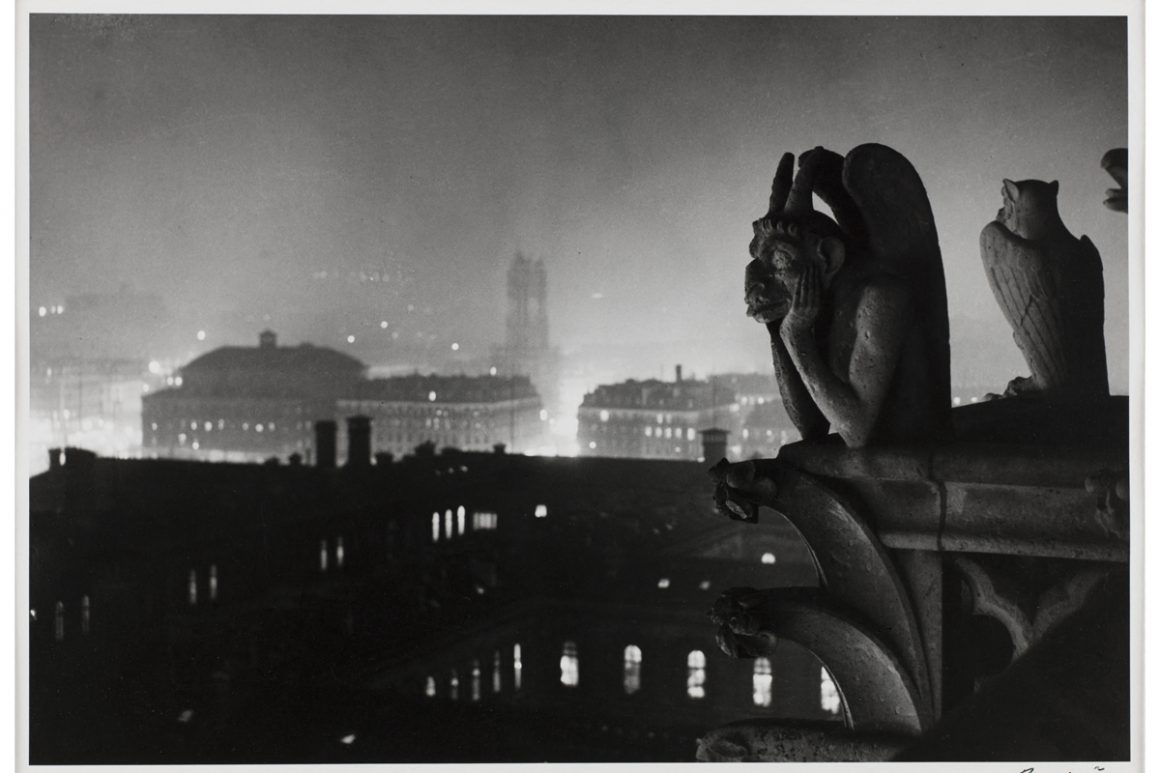

“Night view of Notre-Dame over Paris and the Saint-Jacques Tower.”

Black and white photograph. Gelatin silver print. 1933. Paris, Museum of Modern Art.

From the birth of the cathedrals to the Goth counterculture and fantasy, Gothic art truly has traversed the centuries. In ground-breaking fashion, the Louvre-Lens is presenting its first ever panorama of Gothic art from the 12th to the 21st century, from its emergence through to the neo-Gothic style and right up to the “Goths” of today.

Gothic art is closely associated with the age of the cathedral builders. As the first pan-European movement, it inspired exceptional artistic forms endowed with unparalleled expressive force. Sculptures, art objects, graphic arts, painting, photography, installations and furniture are gathered here in a journey through some 200 works of art. Together they reveal the recurrences and continuity of these Gothic languages, which blossomed during medieval times, came to life again in the 18th and 19th centuries, and still inspire us now. But where does the word Gothic come from? Why is this colourful art today associated with a dark aesthetic of black, night and the fantastic? How can this endlessly recurring attraction be explained? This chronological journey is interspersed with forays into specific topics, touching on the Gothic script, music, film and literature. It is an immersion into history and into society’s collective imagination to understand the origins and singularity of the Gothic movement: unique, multifaceted and very much alive today.

sculpture, Paris, Louvre Museum, Department of Sculptures

© GrandPalaisRmn (Louvre Museum) – Tony Querrec

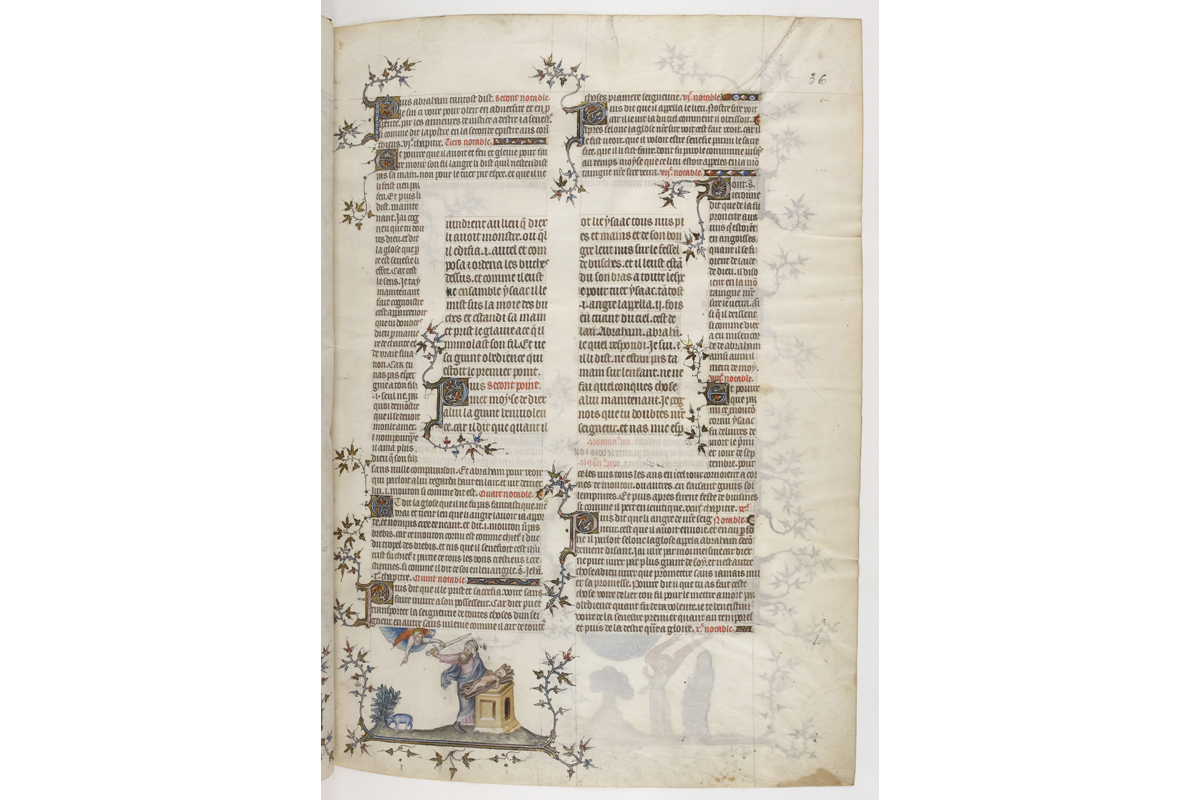

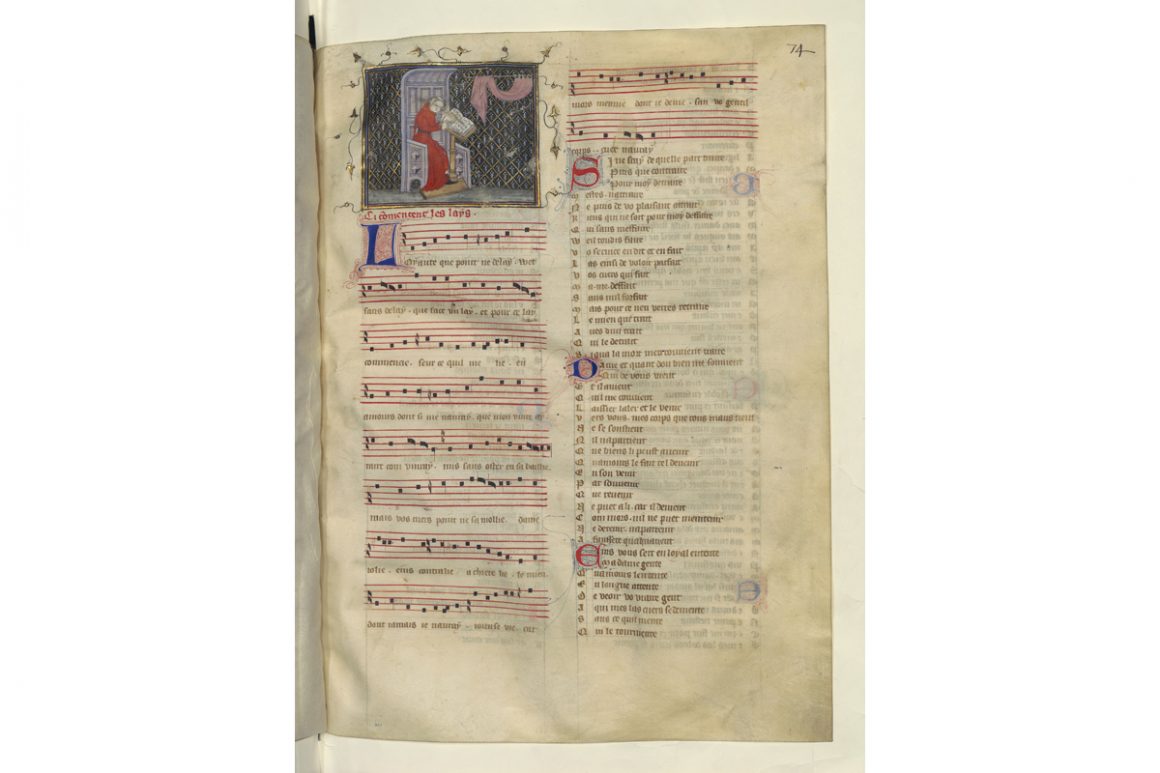

The word “Gothic” is intrinsically associated with the exceptional artistic period of the medieval cathedral builders. From its birth in Île-de-France and Picardy in the 12th century until today, Gothic, and later neo Gothic, art has led to the creation of a multitude of exceptional artistic forms, whose expressive force has traversed the centuries. Its beauty, variety and imposing nature are a source of wonder, as are its motifs, humanist elegance, fantastical evocations and the way in which it accompanies incredible technical prowess in construction. Encompassing all the arts, from architecture to sculpture, stained-glass windows and even illuminated manuscripts, the Gothic art of the Middle Ages offers each of us a different facet depending on our sensibilities.

What is meant today by “Gothic”?

At its origins, it is considered to differ from Romanesque art through its humanist and harmonious aspects, which developed out of French and European research, in particular the scholarly traditions of the monks and artists in Cluny, Saint-Denis and the Meuse Valley. As such, from the 1200s, one single European language began to spread, fed by the intellectual and artistic power of the capital city of the kings of France, before a new trend, even more monumental, was established at the court of King Louis IX, future Saint Louis, later expanding and driving European artistic creation.

© Louvre-Lens – F Iovino

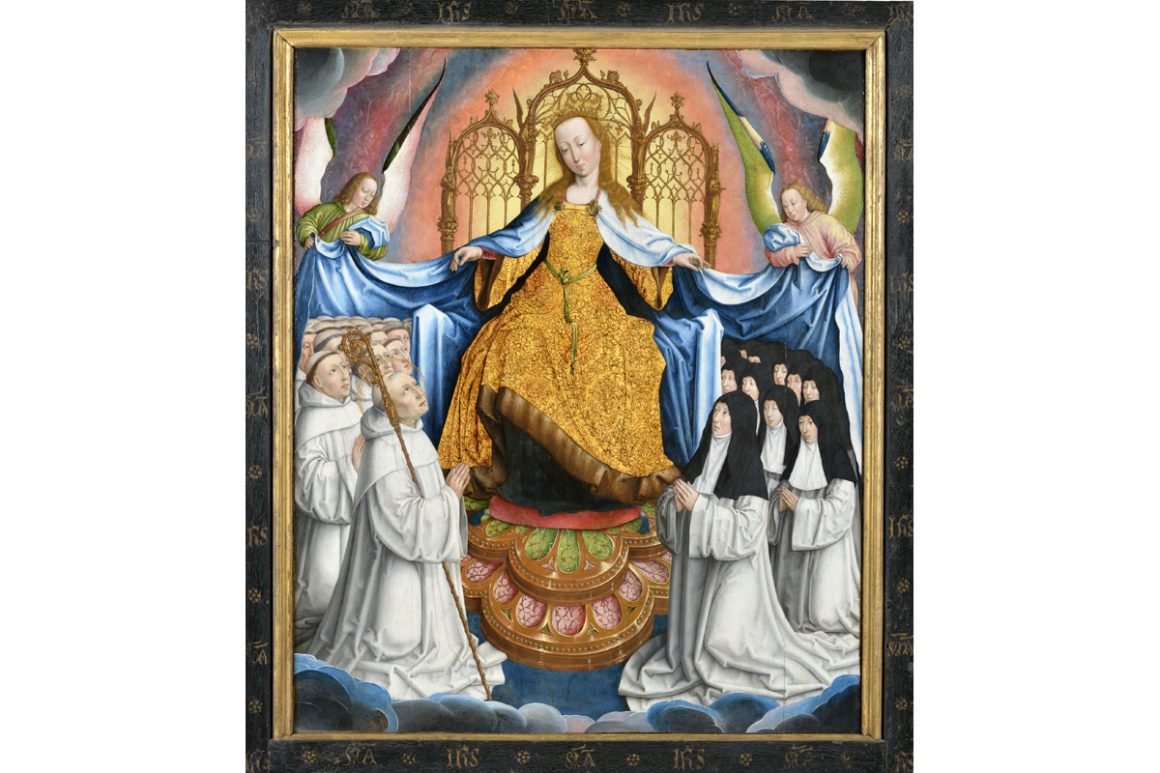

The creativity and skilled crafts that accompanied the art of cathedrals were also adopted by artists working for monarchs and powerful people of the time. Gothic art came to define the era. Varied and independent centres began to appear. Alongside the Gothic architecture of great cathedrals and the conquest of height, a naturalism in the representation of people and plants was born from the encounter between French tradition and sculptors from Northern Europe. In addition, artistic research coming out of Italy and Avignon around 1400 led to international exchanges of Gothic art, whose flexibility and virtuosity charmed courts throughout Europe.

Through masterpieces made of stone, marble and alabaster, as well as precious materials such as ivory and illuminated parchments, we can identify the characteristics from which neo-Gothic art and the collective imagination of the 20th and 21st centuries later drew their definitions of Gothic art.

© Louvre-Lens – F Iovino

An explosion of shapes and decorative diversity marked the 15th century and then the early 16th century, a movement that for some years now has been recognised as “Renaissance Gothic”. Its collection of imagined notions, particularly in the domain of Germanic and Brabançon art, was favourable for the creation of a bestiary and gargoyles, which remain profoundly anchored in the Western imagination, not to mention the script, with its straight lines, ascenders, descenders and crests, and whose immediately recognisable elegance is found in books and charters, as well as inscriptions engraved in stone.

How many of us know that the word“Gothic” emerged after the movement it refers to? The word first appeared in the 15th and 16th centuries as part of the Italian Renaissance and was used (though with a surprisingly derogatory tone) to designate the rupture caused by the return to an Antique style after several centuries of flamboyance. However, its use continued in the arts, both in the late Gothic period, known as Renaissance Gothic, and in its coexistence with the birth of classicism.

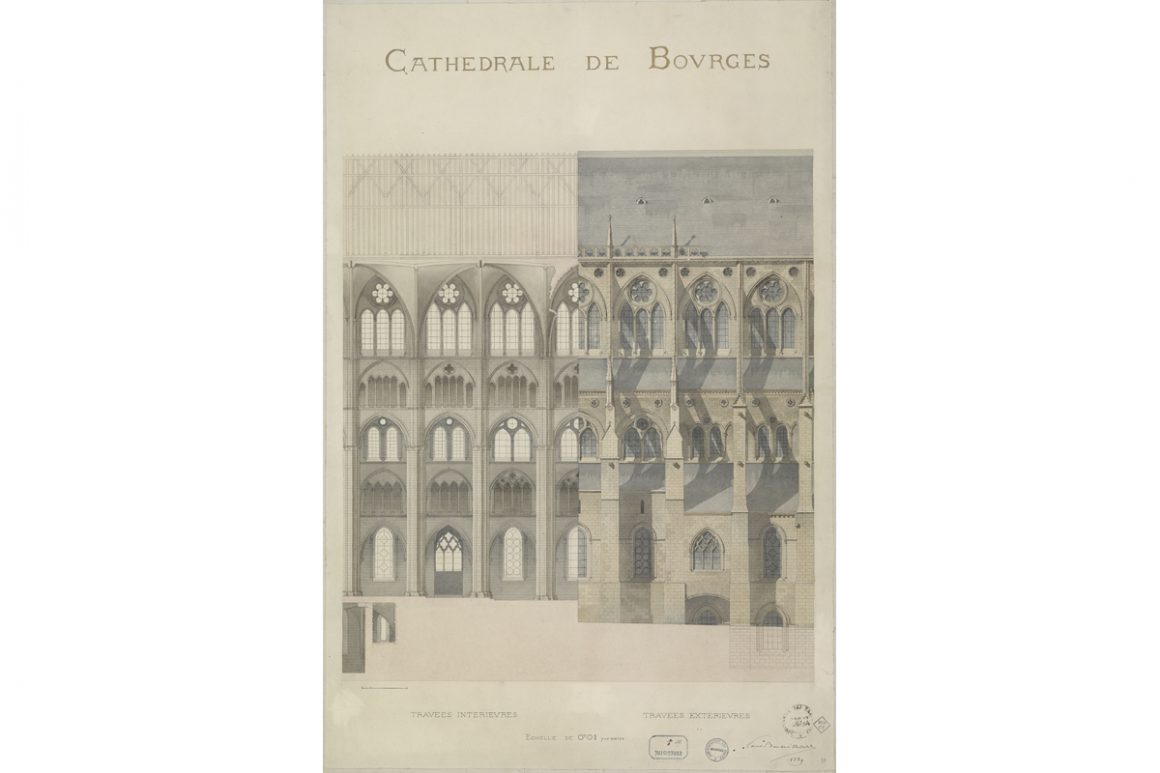

ink and wash on vellum paper, Reims, Museum of Fine Arts

© CC BY-SA 2.0 / Christian Devleeschauwer

A dark, almost black-and-white aesthetic soon came to be associated with Gothic ruins in England. Gradually, from the 18th century, and particularly in the 19th century, Gothic art was not only an art of colour but also took on an affiliation with black. The Gothic style was once again celebrated for its inventiveness and was studied by historians and artists who tapped into it as a model and resource. The author Victor Hugo and architect Viollet-le-Duc contributed to the revaluation of cathedrals, many of which (such as Notre-Dame in Paris) were undergoing major restoration works at the time. The 19th century in particular was that of the Gothic Revival and the appreciation of Gothic architecture as expressed by historian John Ruskin. From England to France and Germany, but also in North America, or even occasionally in Asia, artists from all disciplines, including the industrial arts, began to turn towardsthe “neo-Gothic”.

As this occurred, and especially in the 20th century, the themes and motifs of the Gothic style were picked up and even appropriated by ideological and political movements. Modernist artists, in literature, plastic arts and film, also drew on it for avant-garde inspiration. In contemporary times, the word “Goth” has come to be associated with the counterculture and with punk and metal music. Fantasy, video games, fashion or even contemporary art – especially Digital Gothic and Gothic Futurism – have demonstrated the importance of a continually reinvented collective imagination, right up until today. For artists, the Middle Ages are now, more than ever, a contemporary art.

Paris or Dijon, attributed to Henri Bellechose or Jean Malouel, Small Round Pietà, around 1400-1415, painting and gilding on walnut wood, Paris, Louvre Museum © GrandPalaisRmn (Louvre Museum) /alexandre.dinaut

SCENOGRAPHY: A VOYAGE THROUGH THE GOTHIC REALM

The aim of the exhibition scenography is for visitors to “experience the Gothic realm” Beginning with a nod to Notre-Dame in Paris and its rose window, the exhibition visit takes the shape of a cathedral floor-plan, with its nave and side aisles. Architecture, luminosity, colours: throughout the various sections, it evokes the codes of Gothic styles and how they have evolved over time.

A series of Gothic arches punctuates the spaces in rows until reaching a transition point, just like the cathedral’s choir. A succession of galleries gradually develops into a black-and-white aesthetic, resonating with the movement’s duality and rich diversity.

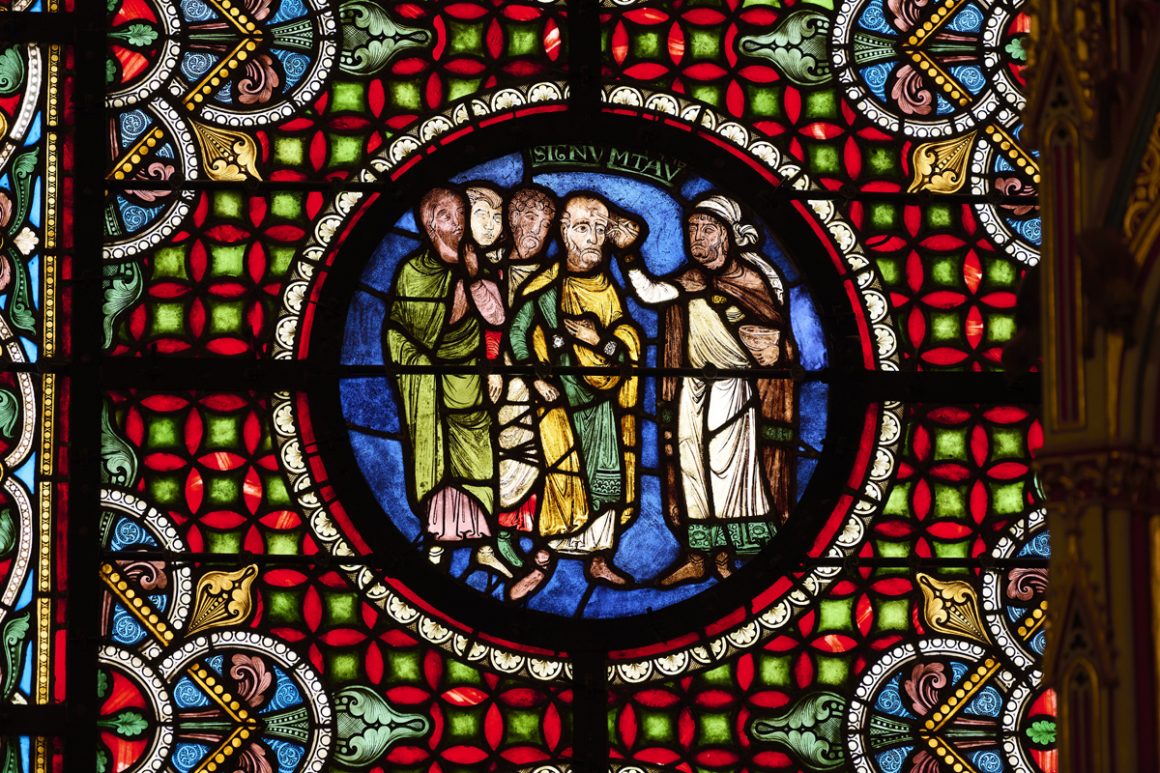

Museum of Decorative Arts © City of Strasbourg Museums / M. Bertola

Period Rooms and Gothic Worlds

Cross-chronological spaces throughout the exhibition visit offer forays into specific topics.They invite visitors to explore the prolific worlds of Gothic scripts, music and dance, as well as colours, including black and white, that still feed our collective imagination today.

Period rooms offer visitors the opportunity to discover two interiors, one after the other, demonstrating the heritage and vitality of Gothic style. The first is an exceptionally well-preserved entire neo-Gothic office, acquired by the Musées de Strasbourg. The second is acontemporary Gothic room-salon, with its bookshelf, music and artworks. It was recreated with the help of Christine and Thérèse, two participants in the Goth subculture who are involved in the organisation of Goth cultural events in the Hauts-de-France and Belgium.

Museum of Decorative Arts (MAD) © Les Arts Décoratifs Christophe Dellière

THE EXHIBITION

THE 12TH CENTURY, THE BIRTH OF GOTHIC ART: TOWARDS AN ARTISTIC LANGUAGE SHARED ACROSS EUROPE

In the 12th century, the art that would become known as “Gothic” emerged out of a favourable context of urban and economic growth. It was also a period of centralisation and strengthening of French power in Paris from King Philip Augustus (1180–1223) to Louis IX, known as Saint Louis (1226–1270). The technical advances that occurred in architecture and the stone column-statues of cathedral portals were accompanied by a new system of thought. The Gothic movement is a form of humanism that marked a systematic return to the models of Antiquity, thus departing from the Romanesque art that preceded it.

1889, Charenton-le-Pont, Mediathek des Kulturerbes und der Fotografie

© Ministerium für Kultur – Mediathek des Kulturerbes und der Fotografie, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Bild GrandPalaisRmn

In only fifty years, from around 1150 to the 1200s, artists throughout Europe developed one and the same art that drew on the innovations of Gothic sculpture in the Île-de France and on the scholarly and harmonious elegance of the sculpted art of the Meuse Valley (in modern-day Belgium, around Liège).

In Lens, midway between the Meuse Valley and the earliest great Gothic cathedrals of Île-de- France and Picardy, it is interesting to examine the phenomenon of how the “1200s style” developed, the initial foundation of a Gothic art that would evolve over later centuries.

- The beginnings of Gothic art

- Regions of the North: The art of the Meuse (modern-day Belgium)

- “1200s Style” and High Gothic: A European movement

Head of a statue of a Magi King, around 1258, Paris,

Cluny Museum – National Museum of the Middle Ages

© GrandPalaisRmn (Cluny Museum – National Museum of the Middle Ages) / Michel Urtado

THE 13TH CENTURY, PARISIAN MONUMENTALITY: A MODEL FOR EUROPE

It was undoubtedly around 1240, at the time of King Louis IX, known as Saint Louis (1226– 1270), that France became recognised as model to be followed. France and Paris set the tone in terms of artistic taste, clothing fashion and gastronomy. Royal authority and the artistic skills in Paris led to the emergence of a new, unique style that was powerful and refined, and that dominated and replaced the “1200s style”. This elegance was inspired by the model of the court. In sculpture, it was notably expressed through almond-shaped eyes and narrow eyelids. The trend further developed in Paris after 1300 under the reign of Philip the Fair (1285–1314). A formidable sovereign, he obtained the canonisation of his grandfather Louis IX, that is, recognition by the Pope of his status as a saint. Meanwhile, Paris was becoming Europe’s intellectual capital and an epicentre for trade and art, including ivory carvings, which are one of the few artistic productions still conserved that were not religious.

- Construction of the great Gothic cathedrals in the 13th century (Rayonnant Gothic architecture)

- The stylistic contribution of artists from Northern Europe

- Gables and pinnacles of every size

- In search of a lost Italian Gothic style…

© Malo Chapuy – courtesy of Mor Charpentier, Paris

CIRCA 1400, SPLENDOUR AND SOFTNESS: INTERNATIONAL GOTHIC

Although it is incorrect to speak of a single Gothic style throughout the centuries, at certain periods a common European artistic language did nevertheless develop.

The 1400s were especially interesting in this regard. After a strong Parisian influence from the 12th to the 13th centuries, new formulas were developed in the 14th century. German architecture displayed great expressiveness, while English architecture was characterised by decorative one-upmanship.

Artists from the North aimed for a faithful depiction of nature while those from Italy were more likely to draw on models from Antiquity. Exchanges between the two gave rise to remarkable creations, in particular in Avignon with Simone Martini (1284–1344) around 1330–1340.

This circulation of artists and models accelerated after the Black Death in 1348. Royal and princely commissions increased in France and Europe. This is now referred to as International Gothic. It is the final common Gothic language prior to the Renaissance and the triumph of the model of Antiquity in Quattrocento’s Italy (from 1400 to 1500).

around 1508, oil on wood, Douai, Chartreuse Museum

© City of Douai, Chartreuse Museum / Photographer: Image & Son

CIRCA 1500: FLAMBOYANT GOTHIC, LATE GOTHIC OR RENAISSANCE GOTHIC?

What is now known as Late Gothic, from the late Middle Ages, varies in time and space but can be characterised by its particularly dynamic forms and striking visual effects. In France, where the appreciation for straight lines and circles persisted long after the 13th century, curves began to dominate around 1400, and today we call this style Flamboyant Gothic.

Around 1500, and for the forty years that followed, this artistic language was used at the same time as that of the Italian Renaissance. This is why recently the proposal was put forward to consider the term “Renaissance Gothic”. At the time, the art we today call Gothic was seen as anything but old-fashioned and was instead thought of as “modern” by its commissioners and French artists, because it was innovative and did not draw on the past – as opposed to a return to Antiquity.

- Flamboyant Gothic

- The Gothic bestiary

- Brabantine Gothic

Lamp of the Archangel Saint Michael, 1830, Paris, Louvre Museum

© Louvre Museum, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn – Martine Beck-Coppola

REDISCOVERING GOTHICISM: HISTORY, NOSTALGIA AND LEGENDS

The rediscovery of the Middle Ages began in the late 17th century in England and France. It took the form of a nostalgia for Gothic architecture and developed around two principal ideas: a fascination for an imagined past and the reappropriation of national cultures.

In England, the birth of a literary genre – the Gothic novel – was inspired by the dark aesthetic of ruins and medieval castles in which the terror-filled intrigues were set. In architecture, famous authors built their residences out of a nostalgia for a national Gothic style: Strawberry Hill (1750–1790) for Horace Walpole (1717–1797) and Fonthill Abbey (1796–1813) for William Thomas Beckford (1760–1844).

In France, the rediscovery grew out of collections made by history enthusiasts. Early historical research was undertaken by François-Roger de Gaignières (1642–1715), an antiquarian who was fascinated by the history of the French monarchy.

In the first half of the 19th century, this rediscovery provided new myths and made people aware of the need to preserve heritage, brought to attention by Victor Hugo (1802–1885) and Prosper Mérimée (1803–1870). Alongside this, artists drew inspiration from the Middle Ages to create a new art, the neo-Gothic.

- Ruins, gardens, chiaroscuro: Gothicism is Romanticism

- The Gothic novel: The emergence of Gothic noir

- From women collectors to the theatre of Victor Hugo: Elevating the Gothic

oil on canvas, Paris, Cluny Museum — National Museum of the Middle Ages

© GrandPalaisRmn (Cluny Museum – National Museum of the Middle Ages) / GrandPalaisRmn image

GOTHICISMS IN THE 19TH CENTURY: THE BIRTH OF THE NATIONAL MONUMENT

In Europe and France, the 19th century coincided with the emergence of the notion of national heritage. From the study of history, awareness was growing of the need to preserve old monuments, such as Gothic cathedrals, that had simply become part of the landscape. This growing awareness was also noticeable in England and Germany with the reconstruction of the Palace of Westminster in London (from the 1840s to the 1870s) and the completion of Cologne Cathedral (1880).

Early on, Victor Hugo (1802–1885) called for a law to protect major historical edifices. When Prosper Mérimée (1803–1870) became Inspector-General of Historical Monuments in 1834, he participated in the creation of the Commission for Historic Monuments in 1837. In 1843, he tasked architects Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Lassus (1807–1857) and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879) with the restoration of the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. These men all contributed to the development of policies to protect and restore heritage and create museums. They were also instrumental in the success of a decorative and architectural style: the neo-Gothic.

- The Musée des Monuments français and the Musée de Cluny: The history of Gothicism for a new collective notion

- Victor Hugo and Notre-Dame de Paris

- The Notre-Dame de Paris restoration project in the 19th century

- The rebirth of the cathedrals: A medieval and modern myth

- Cathedrals and gargoyles

- Gothic architecture at the museum

Sarah Bernhardt, Inkwell: self-portrait as a chimera, 1880, patinated plaster, Paris, Musée Carnavalet CC0 Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet – History of Paris

© Louvre-Lens – F Iovino

THE GOTHIC REVIVAL: GOTHICISM FOR THE INDUSTRIAL ERA, FROM CATHEDRALS TO SKYSCRAPERS

The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century marks the beginning of our modern society. The Gothic Revival began in Victorian England (1837–1901) out of a reaction to the prevailing classicism and advocated a return to a Gothic style and a legendary medieval past. With the rise of international exchange and within a context of colonial expansion, a global Gothic style was born that blended with local creations, from the United States to India. The neo-Gothic, beginning after the Industrial Revolution, proposed a new art of living, which reinvigorated visual forms, notwithstanding its historicism. It was a coming together of Gothicism and modernity. In Paris, architect Louis Auguste Boileau (1812– 1896) first used a metal structure for the construction of the Saint-Eugène Church in 1855, and Anatole de Baudot (1834– 1915) was the first to use reinforced cement for the Saint-Jean-de-Montmartre Church (1894–1904). Alongside this, the quest for elevation of medieval architects inspired the verticality of skyscrapers that were appearing in the United States. Decorative Gothic elements were continuing to stir imaginations, such as for Catalan architect Antoni Gaudi (1852–1926) who began the project of the Sagrada Familia (1882–) in Barcelona, which is still ongoing.

- The Gothic Revival: The rebirth of Gothicism in England and Douai with Augustus Pugin

- PERIOD ROOM – Neo-Gothic living: Neo-Gothic objects and interiors.

- Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Baudelaire and Sarah Bernhardt: The first Goths?

- The 20th century, Gothic structures and the ordeal of the World Wars

- The Gothic realm in film

video game 3D created using the Unity engine

© ADAGP, Paris, 2025

“EMANCIPATORY MIDDLE AGES”* AND GOTH SUBCULTURE

Futurist Gothic**, Tropical Gothic, Digital Gothic… A love for things Gothic resonates with current preoccupations. Its resurgence falls within a multistranded historical context: Gothic noir, continuing from the 18th and 19th centuries, and the reinvention of medieval forms, combining virtuosity and technology. Gothic noir creations revitalise the fantastique, the monstrous and even the macabre; skulls, mythical monsters, and gargoyles, of course, are featured, by artists from Brassaï to Jill Mulleady, to say nothing of Batman. Popular culture and contemporary art are also permeated with medievalism, an imagined history that inspires music, film, television series, video games and role playing, as well as fashion.

The Gothic realm provides artists with an endless source of creativity. It is a way of responding to life’s basic emotions and dealing with the sometimes dark torments of the human soul. By playing on but also laughing at fears, it allows us to go beyond our worries and acknowledge difference. Faced with today’s crises, seen as a new form of apocalypse, 21st-century artists are revisiting an invented Middle Ages, one marked by battles but that also sets out an inspiring model for creating and living differently. The Middle Ages and the Gothic are forms of art more contemporary than ever.

- PERIOD ROOM – Being goth

- Gothic Forever

*From Thomas Golsenne ans Clovis Maillet’s book

** Expression of the artist Rammelizee (1960-2010)

Paris, National Library of France © BnF

Thematic rooms

Is the Gothic style colourful or black and white?

- Colour is practically everywhere

- Black, white and macabre

A complete break from the Renaissance: What does “Gothic” refer to?

What is the Gothic script?

Music and dance

BnF – Department of Prints and Photography © BnF

Exhibition curators:

General curator: Annabelle Ténèze, director of the Louvre-Lens

Scientific curator: Florian Meunier, chief heritage curator at the Department of Art Objects, Musée du Louvre

Scientific advisor: Dominique de Font-Réaulx, general heritage curator, specialising in the 19th century, special advisor to the President-Director of the Musée du Louvre

Associate curator: Hélène Bouillon, director of conservation, exhibitions and publications at the Louvre-Lens Assisted by Caroline Tureck, head of publications and documentation at the Louvre-Lens

Scenography: Mathis Boucher, scenographer, Louvre-Lens.

This project was made possible thanks to the support of the Musée de Cluny – Musée national du Moyen Âge, the Cité de l’architecture et du Patrimoine, the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the Musée des Arts décoratifs de Strasbourg.

Wim Delvoye – © Louvre-Lens-F Iovino

Exhibition: GOTHIQUES – Louvre-Lens, France

from 24 September 2025 to 26 January 2026

Louvre-Lens

99 rue Paul Bert

62300 Lens

T: +33 (0)3 21 18 62 62 / www.louvrelens.fr

Open daily from 10am to 6pm, except Tuesday